| 1777 - 4th BATTALION | 1780 - 7th BATTALION | |

|

|

| Township (if known) | 1777 | 1780 |

| Milford Township |

|

|

| Greenwood Township |

|

|

| Milford Township |

|

|

| Greenwood Township |

|

|

| Fermanagh Township |

|

|

| Lack Township |

|

|

| Lack Township |

|

|

| Fermanagh |

|

|

http://www.digitalarchives.state.pa.us/archive.asp?view=ArchiveIndexes&ArchiveID=13&FL=I

Revolutionary War Military Abstract Card File Indexes

|

I Indexes

Iago, John - Imlay, John

Imlay, John - Ingram, Thos.

Ingram, Thos. - Irvin, Andw.

Irvin, Christey - Irwin, Christm.

Irwin, Christopher - Irwin, Wm.

Irwin, Wm. - Ishmal, Thomas

Isinghour, Hichl. - Izard, Jonathan

Graham, Andrew - Graham, James

Graham, James - Graham, Tedekiah

Graham, Thomas - Gramling, Adam

Blough, Abraham - Boatman, Claudius

Porter, Wm. - Potter, Wm.Potter, William - Poultney, John

This is portion of Son of American Revolution Application of William Henry Graham, great-great-grandson of Captain William Graham.

As you notice Captain William Graham military service was in Cumberland County, PA in the 4th Battalion, 1st Company in July 1777 to May 14, 1778. According to Pennsylvania Archives – “Revolutionary War Militia Battalions and Companies, Arranged by County” he would be from Milford Township in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania.

Captain William Graham military record from “Revolutionary War Military Abstract Card File Indexes” you will notice that this confirms that he was in the Cumberland County Pennsylvania Militia 4th Battalion 1st Company. This is during the same time period that James Irwin enlisted into Cumberland County Pennsylvania Militia under Captain William Grahams as a private.

As you will notice in the above military record of General James Potter Brigade that he is returning the Pennsylvania Militia from Camp White Marsh in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania on November 24, 1777 where their 2 month enlisted had expired. (Enlisted Autumn of 1777). Our James Irwin was in that brigade and apparently served in Camp White Marsh.

Below is background and movement to battle at Camp White Marsh during the time that James Irwin was stationed there.

After their October 4, 1777, defeat at the Battle of Germantown, Washington's army retreated along Skippack Pike to Pawling's Mill, beyond the Perkiomen Creek, where they remained encamped until October 8. They then marched east on Skippack Pike, turned left on Forty-Foot Road (present-day Old Forty-Foot Road), and marched to Sumneytown Pike, where they camped on the property of Frederick Wampole near Kulpsville in Towamencin Township.[6]While there, Brig. Gen. Francis Nash died of wounds incurred at Germantown and was buried in the Mennonite Meeting Cemetery. Washington remained at Towamencin for one week, gathering supplies and waiting to see if Howe would move against him.[7] On October 16, Washington moved his forces to Methacton Hill in Worcester Township. After learning of Howe's withdrawal from Germantown to Philadelphia, Washington moved his army to Whitpain, 5 miles (8.0 km) closer to Philadelphia, on October 20.[8] On October 29, Washington's army numbered 8,313 Continentals and 2,717 militia, although the terms of enlistment of many soldiers from Maryland and Virginia were due to expire.[9] With his ranks reinforced, Washington dispatched a brigade to assist with the defense of Forts Mifflin and Mercer, on the Delaware River.[8] On November 2, at the recommendation of his council of war, Washington marched his forces to White Marsh, approximately 13 miles (21 km) northwest of Philadelphia.[10] At White Marsh, the army began to build redoubts and defensive works.[10]

After the surrender of British Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne after the Battles of Saratoga, Washington began drawing troops from the north, including the 1,200 men of Varnum's Rhode Island brigade, and about 1,000 more men from various Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia units.[11] Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates sent Col. Daniel Morgan's rifle corps, and the brigades of Paterson and Glover.[9] With these additional forces, and the pending onset of winter, Washington had to face the problem of supplying his army.[10] A quarter of the troops were barefooted, and there were very few blankets or warm clothing. Washington became so desperate that he even offered a reward of $10 to the person who could supply the "best substitute for shoes, made of raw hides".[9] Morale was so low and desertion so common that Washington offered a pardon on October 24 to all deserters who returned by January 1.[10]Washington's loss of Philadelphia and inactivity brought criticism from Congress, who pressured him to attack the city. He therefore called a council of war on November 24 which voted against an attack 11 to 4.[12] Nonetheless, Washington rode out the next day to view the British defenses, which turned to be stronger than he had expected.[13]

Capt. John Montresor was responsible for establishing the defenses around British-occupied Philadelphia.

On October 19, Howe withdrew the British forces from Germantown and focused on the defense of Philadelphia. British military engineer Capt. John Montresor supervised the building of a series of fourteen formidable redoubts that began at Upper Ferry, along the Schuylkill River, and extended eastward to the shores of the Delaware River, just north of Philadelphia.[14][15] Howe took advantage of his time in Philadelphia to raise additional forces from the loyalist population in the region. Newly-promoted Maj. John Graves Simcoe reinforced his unit, the Queen's Rangers, which had lost over a quarter of its men at the Battle of Brandywine.[16] William Allen, Jr., the son of notable loyalist William Allen, raised the 1st Battalion of Pennsylvania Loyalists, and was made its lieutenant colonel.[17] Loyalist James Chalmers raised the 1st Battalion of Maryland Loyalists, and was given its command.[18] Recruitment also took place among the city's Irish Catholic population, with the formation of the Irish Catholic Volunteers, and in the counties immediately surrounding Philadelphia.[19] In mid-November, the fall of Forts Mifflin and Mercer effectively ended American control of the Delaware River, and much-needed supplies began arriving at the city's docks, along with 2,000 additional British soldiers.[20]

The weeks with two major armies sitting within miles of each other were not without conflict, and a petite guerre[21] ensued in the no man's land between White Marsh and Northern Liberties. Minor skirmishes between light troops increased in intensity throughout November, with almost daily losses being incurred by both the British and the Americans.[22] In retaliation, on November 22, Howe ordered his troops to set fire to several large country houses in the Germantown area, including Fair Hill, a mansion and country estate that had previously belonged to John Dickinson.[23] Eleven houses in all were burned to the ground, and residents of Philadelphia climbed onto rooftops and church steeples to watch the spectacle.[23] Just one day earlier, crowds had gathered to watch the burning of Commodore John Hazelwood's Pennsylvania Navy in the Delaware.[24] On the same morning the mansions were burned, an earthquake struck Philadelphia, and was felt as far away as Lancaster.[25] On November 27, an aurora borealis lit up the night skies.[26] The two events caused quite a stir among both the residents of Philadelphia and the troops, British and American alike, who took them as an ominous sign of things to come.[27]

By early December, Howe decided, despite having written to Colonial Secretary Lord George Germain requesting to be relieved of his command, that he was in a position to make one last attempt to destroy Washington's army before the onset of winter, and he began preparations for an attack on the American forces.[28] Washington's intelligence network in Philadelphia, led by Maj. John Clark, became aware of British plans to surprise the Americans. According to a historically unsubstantiated story,[29]Howe's movements were revealed to the Americans by a Quaker woman named Lydia Darrah,[30] who overheard British officers quartered in her house discussing Howe's plan, and crossed the British lines to deliver this information to Col. Elias Boudinotof the Continental Army, who was at the Rising Sun Tavern between Germantown and Northern Liberties, attempting to secure provisions.[31] Boudinot immediately relayed this information to Washington,[31] and the Continental Army was ready when Howe, with a force of approximately 10,000 men, marched out of Philadelphia just prior to midnight on December 4.[32] The advance column, led by Lt. Gen. Lord Cornwallis, headed up Germantown Pike. A second column, led by Lt. Gen. von Knyphausen, marched toward the American left.[32]

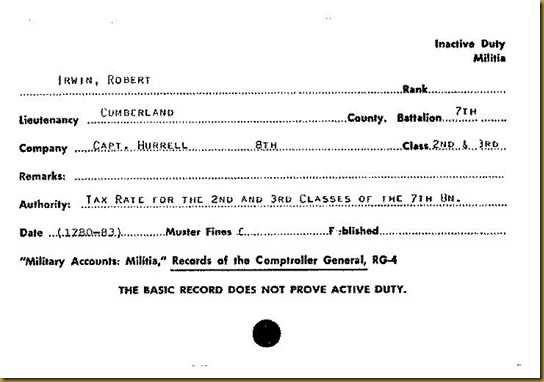

Below is James Irwin Cumberland County, Pennsylvania Militia Records from “Revolutionary War Military Abstract Card File Indexes”. You will notice that on July 14, 1778 James Irwin was delinquent in serving in the militia per order of the council. He was fined 100 pounds. He was assigned from Milford Township in Cumberland County to 4th Battalion 1st Company under the command of Captain Philip Matthies.

On March 12, 1782 James Irwin was called from Milford Township to serve in 7th Battalion 8th Company of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania Militia by order of the council. It appears that he served during this time.

Below is a Revolutionary War Military Abstract Cards of Irwin’s living in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania during the Revolutionary War.

| 1777 - 4th BATTALION | 1780 - 7th BATTALION | |

|

|

| Township (if known) | 1777 | 1780 |

| Milford Township |

|

|

| Milford Township |

|

|

4th Battalion 1st Company – Milford Township

4th Battalion 3rd Company – Milford Township

7th Battalion 8th Company – Milford Township

7th Battalion 6th Company – Milford Township

| 1777 - 4th BATTALION | 1780 - 7th BATTALION | |

|

|

| Township (if known) | 1777 | 1780 |

| Lack Township |

|

|

4th Battalion 7th Company – Lack Township

No comments:

Post a Comment